The Deltan Special Report

A Guatemalan official prosecuted powerful countrymen for millions in unpaid taxes. Soon, he was fired, arrested and charged with serious crimes. Reuters examines the pushback against efforts to end the corruption and impunity forcing many Central Americans to migrate.

BY FRANK JACK DANIEL in GUATEMALA CITY

When Juan Francisco Solorzano Foppa took over Guatemala’s tax agency in 2016, he took on a previously untouchable set of targets: officials, families and companies suspected of bilking much-needed revenue from the government.

The new tax chief purged more than 1,500 tax officers and arrested high-profile suspects, including elders of the country’s tight-knit business class. He wrested an unprecedented $100 million settlement from a major steel company, Aceros de Guatemala S.A., and busted a major hotelier for allegedly forging invoices.

Many here celebrated him for tackling elites long used to getting away with evading taxes. Guatemala is one of the world’s poorest and most unequal countries, with the lowest tax take in Latin America as a percentage of the national economy. But the burly former prosecutor with a buzz cut and a boxer’s nose also made mighty enemies.

Foppa, as the 38-year-old is widely known, this year found himself behind bars, in a case that even his adversaries acknowledge was largely fabricated. His arrest, and 22-day jail stay, was part of an ongoing backlash against some of the leaders of an anti-corruption movement that for a time pioneered efforts to end graft and impunity for powerful elites in Central America.

On May 19, as he drove to the gym, two men in a black SUV with no plates forced Foppa to pull over, he told Reuters. He filmed the encounter and broadcast it via Twitter. The men refused to identify themselves but kept Foppa from driving away. Then, police arrived to arrest him, locking him in the same cell block as a tattooed gang boss Foppa himself had jailed. The gangster, Foppa said, threatened to chop him into pieces.

UNMARKED VEHICLE: After unidentified intelligence agents pulled over his car, Foppa filmed his interaction with the police. REUTERS

At a later court hearing, a police report identified the men in the SUV as intelligence agents from the Interior Ministry. The allegations against Foppa, all of which he denied, were related to efforts he had made to register a new political party; the judge threw out the most serious charges and released him.

The arrest was considered by some here to be a new low, the latest in a series of mounting reactions against a campaign by Foppa and a set of other officials to end impunity for the powers that be. The backlash started with the ouster in 2019 of an innovative United Nations body that targeted graft for more than a decade. It intensified this year when the attorney general fired or demoted a series of high-profile prosecutors, including another well-known anti-graft investigator, whom she has sought to arrest and charged with offenses including breach of duty, abuse of authority and conspiracy.

The pushback, Foppa and some others in the anti-corruption camp concede, may have in part been self-inflicted. In their zeal to prosecute wrongdoing, they used hard tactics, pressing charges when settlements may have been reached, angering even some moderates once disposed to support them.

“We were intransigent,” Foppa told Reuters.

Foppa’s predicament is part of a broader struggle afoot in Central America over efforts to end the widespread misrule that has destabilized the region and stoked an exodus that’s contributing to the migration crisis at the U.S. border.

Guatemala was traumatized by a four-decade civil war, pitting right against left along Cold War fault-lines, that ended in the late 1990s. In the following years, some Guatemalan elites, who generally supported right-wing forces, accepted efforts at reconciliation and reform with the left, largely supported by the poor. The steps included the investigation of shadowy groups, sometimes linked to wealthy families, that influenced the military, courts and other power centers.

Now, though, “the pendulum is swinging in the opposite direction,” said Salvador Paiz, a former supermarket executive who said he supported the anti-graft movement until he himself was targeted by prosecutors in a controversial campaign-finance case.

The setbacks of the graft-busters have roiled many Guatemalans.

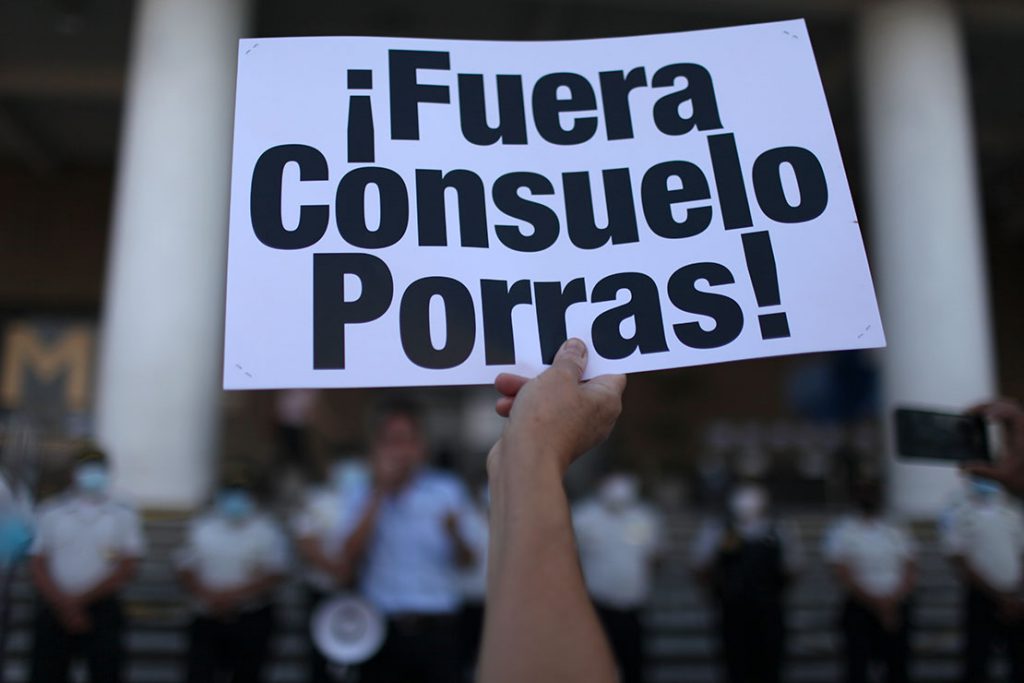

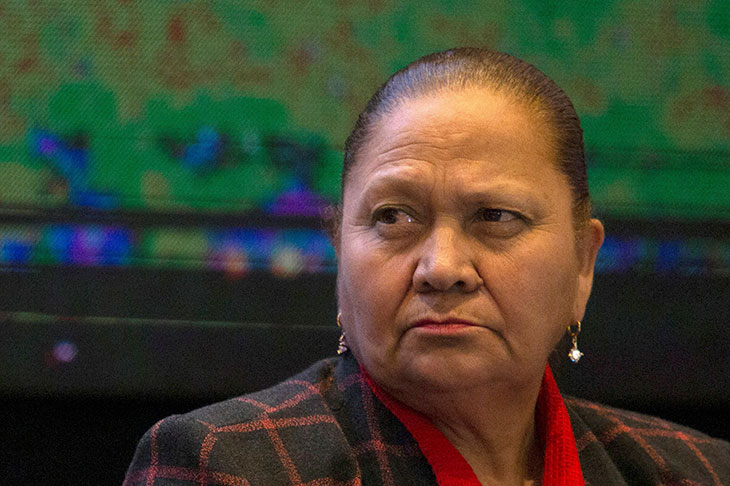

Protests erupted across the country in July, after Attorney General María Consuelo Porras, an ally of conservative President Alejandro Giammattei, fired the anti-graft prosecutor. Five former prosecutors have left for the United States, joining a former president of Guatemala’s top court and two former attorney generals. At least three have applied for asylum. All have said they fear criminal charges at home.

Porras’s office, in a statement, said the dismissal followed an “objective and technical” investigation by qualified criminal prosecutors. It said Porras has strengthened measures to combat corruption and that ongoing probes are conducted in an “objective and impartial” manner, without political interference.

President Giammattei, in an interview with Reuters earlier this year, said the anti-graft effort of years past had become an ideological campaign used by left-leaning prosecutors to unfairly target the right. “Everybody has a right to their own ideology,” Giammattei told Reuters. “The problem is when you transfer that ideology to your actions, and worse when you are in charge of justice.”

Similar arguments against anti-corruption campaigns have prevailed elsewhere in Central America, fueling tensions reminiscent of those that divided the region during the Cold War. The governments of Honduras and El Salvador also recently dismantled anti-graft bodies and dismissed prosecutors and judges emblematic of campaigns against corruption there. The trend alarms foreign governments, democracy advocates and human-rights activists, especially those worried about increasing inequality in the region and the record number of migrants who have fled it recently.

“Strong democratic institutions and rule of law are essential,” said Hans Magnusson, Sweden’s ambassador to Guatemala, in an interview. “Impunity and corruption,” he added, “rob Guatemalans of opportunities and worsen inequality, with the all-too common result that they leave.”

Last month, Hondurans voted to end more than a decade of rule by the conservative National Party, whose government scrapped anti-graft initiatives even as it was rocked by corruption and drug-trafficking scandals. In a nod to the discontent, Xiomara Castro, the leftist president-elect, said she would reverse those policies, empower prosecutors and narrow inequality.

Though Central American economies are rebounding from the Covid-19 pandemic, food shortages have risen almost three-fold since 2019, with 6.4 million people in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador now living with hunger, according to the United Nations World Food Program. In the 12 months ended September 30, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents apprehended 280,000 Guatemalans attempting to cross the southern U.S. border, greater than any other year on record.

They’re leaving places like Huitzitzil, a poor hamlet lodged between palm and banana plantations along the Pacific coast. On a recent visit, residents told Reuters that at least half a dozen of their neighbors had left for the United States in the previous two weeks. Some villagers, like Ileana Pérez, were anxiously awaiting word from relatives on the perilous trek to cross the U.S. border illegally.

A street vendor and single mother of three whose husband was murdered in a bar brawl, Pérez said hardship in the village has grown. She is frail and recovering from a minor stroke. Government officials never answered her application for a pandemic subsidy, she said. Guatemala’s Social Development Ministry said it couldn’t determine what happened to her application for aid.

Pérez was desperate to hear from Jenifer, a 21-year-old daughter who struck out for the United States with a cousin in late October. Jennifer last touched base a week earlier, Pérez said, when she sent a photo from the desert along the U.S.-Mexico border. “She left to try to help me,” Pérez said, weeping.

Earlier this year, Reuters chronicled how corruption and alleged government complicity in illegal rackets weaken local economies in Honduras and undermine efforts to ensure the rule of law. In Guatemala, Reuters spoke to dozens of business leaders, government officials, diplomats and investigators about the pushback against anti-graft efforts. Their assessment largely echoes that of Foppa, the former tax chief, who called the campaign against him and like-minded colleagues a deliberate “process of criminalization.”

“It’s been continuous,” he said, “permanent.”

“Embers of the civil war”

Foppa’s family history is entwined with that of Guatemalan politics.

His grandfather helped create the national health institute under leftist president Jacobo Arbenz, whose 1954 ouster in a U.S.-organized coup triggered a sequence of events that later led to civil war. Foppa’s father, a leftist guerrilla fighter, died in the conflict. His grandmother, a renowned feminist poet, was kidnapped and never seen again, one of about 200,000 people who died or disappeared during the war.

As the country worked to normalize at the turn of this century, peace agreements quelled restive guerrillas. In 2006, the government allowed the United Nations to set up a team of independent investigators, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala. The agency, financed mostly by the U.S. and European governments, became a model for anti-graft efforts across Central America. Known by its Spanish-language initials, CICIG, it put one sitting president, and two of his predecessors, behind bars over the next decade.

One of CICIG’s early investigations jailed Giammattei, the current president, for his period as director of the national penitentiary system. Prosecutors working with the agency detained him on charges of “illicit association,” alleging he was part of a criminal ring within security forces that killed seven inmates in a prison raid. A court later threw out the investigation of Giammattei, citing a lack of evidence, and freed him.

Foppa at the time was starting his law career as an assistant to a prosecutor in the attorney general’s office. He was part of a generation of young attorneys eager to help Guatemala move forward. He prosecuted homicides and leaders of increasingly violent street gangs.

In 2013 he was promoted to create a new criminal analysis unit. There, he helped uncover a racket within the customs department of the tax office, convicting a ring that smuggled millions of dollars of cigarettes and whiskey.

Soon, he worked on a big joint effort with CICIG.

The probe investigated a special telephone line, dubbed “La Linea,” that customs officials had established for in-the-know importers to call and pay bribes instead of customs fees. In 2015, prosecutors had enough evidence to charge then-President Otto Pérez Molina, a former general, as the ringleader of the scam. Stripped of immunity by Congress, Pérez Molina resigned and has been in pretrial detention ever since.

In an interview in the garden of the prison where he is awaiting trial, Pérez Molina denied wrongdoing. As president, he said, he didn’t manage the customs office and wasn’t aware of the scam.

The case prompted huge anti-graft protests and was a watershed in the fight against impunity. “La Linea unbottled the immense corruption corroding Guatemala,” said Richard Aitkenhead, a former finance minister who helped negotiate agreements that ended the civil war.

The evidence gathered in the investigation later led Foppa and colleagues to suspect tax evasion by Aceros de Guatemala, the steelmaker. Some of the government’s own revenue officials, prosecutors alleged, were helping Aceros make large tax bills vanish. Prosecutors soon arrested top Aceros executives and senior tax officials. The company and the executives have denied wrongdoing.

In March 2016, a new government named Foppa tax agency chief. His rising profile mirrored the changing nature of the graft battle in Guatemala.

Early corruption convictions had centered mostly on political wrongdoing. Foppa’s tax cases broadened the scope, hurting the business community, long dominated by a handful of wealthy clans. In a widely shared Facebook post at the time, Ricardo Méndez Ruiz, head of a conservative think tank, called Foppa’s appointment “a serious mistake.” Foppa, he warned, would conduct “fiscal terrorism” against elites.

Méndez Ruiz told Reuters his post was prescient. Foppa “put in prison every businessman that he saw, turning administrative issues into criminal cases,” he said. Foppa himself has since conceded that at times he was too aggressive.

Upon taking the agency’s helm, Foppa dug further into Aceros. He told the steelmaker it owed $100 million in back taxes, fines and interest. When the company resisted, Foppa said, he told deputies to “send in the administrators,” putting the agency in charge of the company’s books. As soon as tax agents marched into Aceros’ offices, he said, the company’s banker called, pleading for the crackdown to be lifted.

Marco Augusto García Noriega, an Aceros lawyer, told Reuters the company paid the fine so it could get on with business. He denied Aceros ever broke the law. “They never proved it,” he said.

The penalty, the largest tax fine in Guatemalan history, rattled elites.

Next, Foppa went after a family-owned hospitality empire. Its flagship property is the Camino Real, an imposing modernist hotel that has long been an icon of high society in Guatemala City, the capital. The company, Hotel Camino Real SA, for years had filed false invoices to tax authorities, Foppa’s investigators alleged, dodging payments worth $2.7 million.

At first, Foppa said, Camino Real filed yet more phony invoices in efforts to patch over its shortfalls. When the company failed to file authentic paperwork, he said, Foppa sought the arrest of Carlos Enrique Monteros Castillo, the company’s owner and a patriarch of Guatemala’s corporate elite. Police in July 2016 arrested the then-71-year-old executive as he stepped off an international flight at the Guatemala City airport.

As with Aceros, Foppa sent agents into the company’s finance department, housed in an annex to the marquee hotel. Within days, Camino Real paid the balance, plus interest and fines, totalling about $5.8 million. Monteros Castillo, who pleaded guilty, was freed.

Camino Real didn’t respond to a Reuters request to discuss the episode. A family spokesperson said Monteros Castillo declined to comment.

Foppa pursued yet more targets, culminating in dozens of sanctions and $280 million in reclaimed taxes. Images like that of the hotelier detained by police seized the business community’s attention. “What hurt them most was the exposure,” said Foppa. “These are things they will never forgive.”

Foppa said he was hard on those close to him, too.

He told his mother, Silvia Solorzano Foppa, to get up-to-date on her own taxes, three years past due, with arrears of about $2,300. She confirmed the incident to Reuters, saying her son issued his order to her on a holiday.

“It was Mother’s Day,” she said.

Foppa also restructured the tax agency. That led to the dismissal or resignation of about a third of its workforce, some of which, he alleged, had helped big business and the wealthy evade levies.

But along with the work of CICIG, the U.N.-backed body, the tough measures increasingly convinced conservatives they were unfairly targeted. “There are plenty of examples showing it,” President Giammattei told Reuters. “These are the embers of the civil war.”

“A monster”

Powerful players in Guatemala began planning a pushback. They found an ally in Jimmy Morales, a comedian turned conservative politician who had recently become president.

In November 2016, investigators from the public prosecutor’s office raided Morales’ official residence, forcing the president out of bed in his pyjamas. The raid, part of a probe into alleged corruption in the presidential guard, was soon followed by the arrest of the president’s son and brother. Prosecutors charged the two with fraud and laundering about $12,000. They denied wrongdoing, and a court later found both not guilty.

Morales didn’t respond to requests from Reuters for comment.

The raid caused yet more opposition to anti-graft efforts, further forging a loose coalition of business veterans, conservative politicians and far-right activists. Then, in August 2017, prosecutors working with CICIG announced an investigation into the financing of Morales’ election. They would later charge five prominent business people, including Paiz, the former supermarket executive, with breaking campaign finance laws. All have denied the charges, which haven’t yet advanced to a trial.

“What hurt them most was the exposure.”

Juan Francisco Solorzano Foppa, former Guatemalan tax chief

The case was perceived by many in the business community as a ploy to undermine Morales. “Did we withdraw support?” said Paiz, describing the community’s waning approval of anti-graft efforts. “Absolutely.”

Two days after CICIG announced the investigation, Morales struck back. In an online video, he declared Iván Velásquez, a Colombian prosecutor who headed CICIG, persona non grata. Morales said he took the measure “in the interest of the Guatemalan people” and “strengthening the rule of law.”

In January 2018, the government fired Foppa as head of the tax agency. The agency’s board, chaired by Morales’ finance minister, said Foppa had missed a revenue goal. The take that year was less than 1% short of the target.

Foppa started a private legal practice.

That August, Morales ordered military vehicles to surround CICIG headquarters. With rows of soldiers behind him, Morales told television cameras that CICIG itself was no longer welcome in Guatemala. He refused to renew its mandate for 2019.

The European Union and the United States criticized the ouster. In a statement at the time, the U.S. embassy in Guatemala said: “CICIG is an effective and important partner in fighting impunity, improving governance, and holding the corrupt accountable.”

Morales’ interior minister fired police officials deemed close to CICIG. With the help of the business community, Giammattei in 2019 was elected to succeed Morales, taking office in early 2020.

Foppa decided to try his own hand at politics. He set up a committee to consider a run for the mayorship of Guatemala City, but failed to become a viable candidate. He also sought the top office of the Guatemalan Bar Association – a position that can influence the composition of high courts – but lost.

His arrest earlier this year followed an effort he made to start a new, center-left political party. It isn’t clear what first led prosecutors to investigate him.

After intelligence agents pulled his car over last May, he said, the men wouldn’t give him any details. When a police patrol pulled up seconds later, the officer had no paperwork and had to have an arrest warrant sent to his phone, Foppa said.

“This arrest was illegal,” Foppa told the judge at the court hearing. He likened the use of anonymous agents to notorious kidnappings conducted by security forces during the civil war.

The case stems from irregularities in the signatures needed for a new party to register in Guatemala. The name of at least one dead person was among those collected by notaries Foppa hired for the effort. Foppa concedes the paperwork contained errors.

Still, attorneys and others familiar with the case say they were shocked by the gravity of the charges prosecutors initially sought. In addition to a forgery charge, he was accused of “illicit association” and “conspiracy” – charges generally reserved for defendants in organized crime cases like those Foppa himself once prosecuted. The judge later dismissed those charges.

The severe accusations, some of Foppa’s foes say, reflected the ideological rancor gripping the justice system. “He was victim of a monster that he helped create,” said Méndez Ruiz, the conservative think tank director.

Foppa still faces a charge of forgery over the signatures. If the case proceeds and he is found guilty, he could face up to nine years in prison. He denied participating in any effort to fake signatures but said he should have been more thorough in supervising the process.

“It was a mistake to start without being fully in control,” he said.

As Foppa began working to clear his name, Attorney General Porras reassigned other investigators and prosecutors aligned with the anti-corruption movement. In July, she dismissed Juan Francisco Sandoval, head of the prosecutorial unit that worked most closely with CICIG.

Porras informed Sandoval of his firing in a letter in which she accused him of disobeying orders. The letter was leaked to local media and confirmed as authentic by Sandoval. He told Reuters he resisted a request by the attorney general to appoint a prosecutor she wanted on his team, but denies wrongdoing.

Sandoval’s firing led thousands of Guatemalans to protest. Fearing prosecution, he fled for the United States. A Guatemalan court later issued arrest warrants against him.

Following the episode, the U.S. government added Porras to its list of “corrupt and undemocratic actors.” In a statement, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken accused her of “interfering with criminal investigations” and “transferring and firing prosecutors who investigate corruption.”

In its statement to Reuters, Porras’s office said she denies the allegations. Expanded cooperation with the United States on issues including drug trafficking and migration, it said, show the attorney general’s office remains committed to meeting “its constitutional mandate and national and international standards.”

Foppa is still working on his defense and weighing his options as a budding politician. If Guatemala truly wants to end corruption and impunity, he said, officials like him will have to be more flexible, pursuing consensus toward shared goals instead of relentless prosecution.

“There needs to be a type of truce,” he said.

The Backlash

By Frank Jack Daniel

Additional reporting by Sofía Menchú in Guatemala City.

Photo editing: Tomás Bravo

Art direction: John Emerson

Edited by Paulo Prada